Moby Dick Musical and an Analysis on Unconventional Musical Theatre

January 14, 2020

The story lasts 585 pages. It includes action, drama, and a chapter classifying the types of whales, which goes on for “a curiously long time,” the character of Ishmael, played by Manik Choksi says.

The name of the theatrical performance is Moby Dick, written and composed by Dave Malloy, who is also famous for writing Natasha, Pierre, and the Great Comet of 1812.

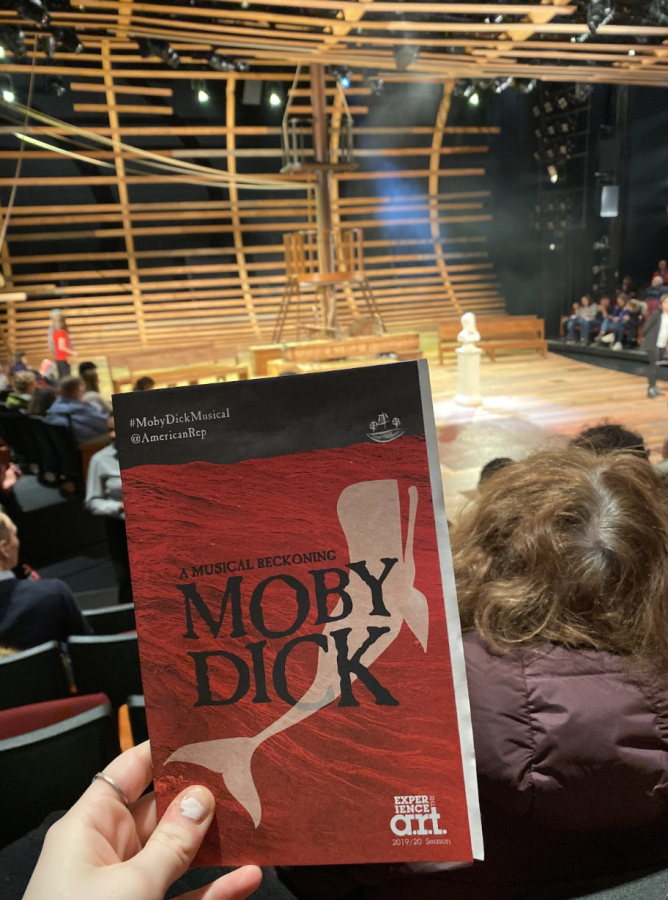

I saw Moby Dick on Wednesday, January 8th, at 7:30 PM and left the ART theatre in Cambridge at 11:00 PM that night. The show is 3 hours and 25 minutes, four acts long, with one fifteen-minute intermission between acts two and three.

As I walked into the ART black box, I was greeted with loud sea shanties and a woman dressed in a gigantic hoop skirt greeting other audience members. The set stretched from less than a foot from the audience to the ceiling. It was a deconstructed ship, with long curved boards running up the wall. The main mast intersected the central upstage, with the bust of Herman Melville, the author of the original book, in center stage. I took my seat, which was in the fifth row of the middle section, and looked above my head. The boards spanned to the back of the house, covering three out of the four surfaces: floor, back wall, and the entirety of the ceiling.

Three ASL interpreters sat four rows ahead of me. They later performed the entire show in ASL, alongside the cast, with as much emotion as anyone on that stage.

As the show began, I was immediately enthralled by the music from the first song.

Dave Malloy is notorious for juxtaposing the instruments, singing, and tone of the show, but in a way that does not take the audience out at all. The most notable example I can give is one which I have heard in both Moby Dick and Great Comet, in which there is a heavy and confusing beat occurring in the background, while the foreground is in both cases, a man of older age, singing gracefully, but with extreme passion. This is notable in the songs “The Quarter-Deck” and “The Private and Intimate Life of the House,” in each musical, respectively.

Malloy’s unique use of ensemble harmony is emotionally captivating. The crew surrounded the audience, and, like many other times throughout the show, sung in beautiful contrast from the pit.

Oh, yes. The pit.

While I’m not sure exactly how many people were in the pit, it couldn’t have been less than thirty. They were mounted upstage right, on three different stories built to look like the three levels of the ship. The instruments stretched from electronic, to violins and double basses, and, while slightly deafening at times, I have never heard more creative and unique music in my life.

Act Two is where it gets interesting.

At the end of Act One, Ishmael comes out and starts talking to the audience, telling us that a ship needs more sailors than the ones they have. Fifteen more, to be exact. He asked for fifteen volunteers from the audience to come down to the stage, wear bright red ponchos, and advised those who volunteered to be comfortable with being wet, and they may experience motion sickness.

While I was not chosen, watching what followed from an audience perspective was captivating. The floors opened, and four, colorful, life-sized lifeboats emerged from the floor. The new sailors were pushed into the boats, and the cast pushed them around in ordered chaos in the song “Stubb Kills a Whale.”

The plot moved forward slightly, while the new sailors watched from onstage, and they were called back after killing the whale to help them squish the sperm.

The cast and new sailors sat in a semicircle and squished what looked like some sort of lumpy white substance in the song “A Squeeze of the Hand.”

Their hands were wiped clean, and at the end of act two, the new sailors were sent back to their seats.

Acts three and four were disappointing. Maybe it’s because of the quick emotional difference, but the plot became less attention-grabbing. “The Ballad of Pip” was the entirety of act three, a group of songs about the young boy aboard the ship, and how he loses his sanity. Many of the songs sounded similar, and as act three melted into act four, it was hard to tell where one song stopped and the next started.

Dissimilar from Great Comet, there was no “hype up” song (I am referring to Preparations, Balaga, and The Abduction) to help the audience get through acts three and four.

I was satisfied with the ending. The attack of Moby Dick was lower energy than expected but was consistent with the moods and emotional stability of the crew.

The last song ended the same way Great Comet ended, very quiet and calm. It was the chanting of “The ship isn’t sinking, the ship is already sunk.” as the cast walked through the side doors.

Moby Dick blew me away. Every person involved in this show could have easily carried it by themselves, but as a team, it became a new dimension of life and activity right in Cambridge, Massachusetts. The visual aspects were a mix of modern and period sets and props, but nothing unconventional took away from the plot or show at all. The combination of modern and old vernacular was effective as well, underscoring dramatization of the harsher scenes, and the lightheartedness of the more fun scenes.

I enjoyed the breaking of the fourth wall and the audience participation. While I understand how many people may roll their eyes, I argue with them where they’re getting their predispositions from. Where is the algorithm on how to create a successful musical? Having a plot, keeping the audience engaged, but what more is there? Why can’t characters break the fourth wall? Or tell jokes to the audience? Or ask how we can apply the messages from 1851 to 2020?

No rule prevents actors from destroying the conventional rules of a musical.

I did find the musical to be too “we live in a society” -esque. When the cast said, “Whales don’t commit hate crimes,” I outwardly sighed. There was much pandering to climate change, race discussion, even equity pays, which was not what anyone in the audience was expecting. This subject is obviously important to discuss and find solutions for, but generally speaking, did not fit with the section of the audience who came to see their favorite book turned into a show.

It almost seemed as if Malloy was using Moby Dick to talk only about social justice–as opposed to subtly hinting at it.

Nevertheless, Moby Dick exceeded my expectations in every capacity. The score, set, puppeteering, and acting were brilliant. I would love to sit for another 3 hours and 25 minutes and watch this unfold.