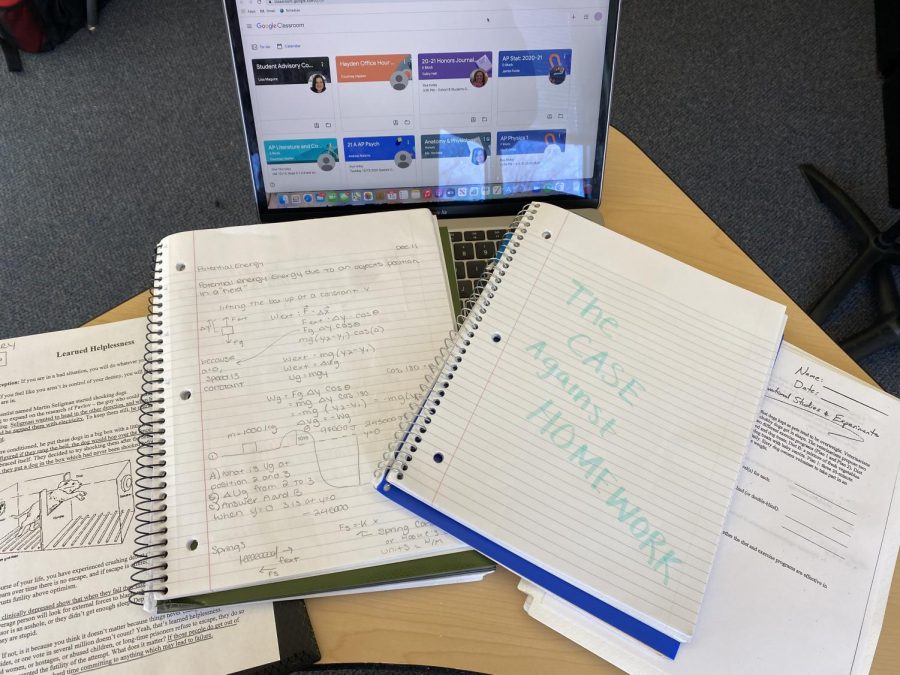

The Case Against Homework

Why homework exists and what we can do about it

December 21, 2020

In 1930, the American Child Health Organization classified homework as a form of child labor. First designed as a punishment for “lazy” students, homework has become an everyday aspect of life for countless young Americans. We have become accustomed to the monotonous problem sets and tedious notetaking, and for many, working at home can take a toll on sleeping habits, mental and physical health, and even our personal relationships. Because there is an inherent numbness to the negative repercussions of homework that have been gradually normalized throughout history, most do not stop and wonder why it is that a country with such plentiful resources continues to educate in this outdated and uncreative way. To put it simply, the educational system in the United States prioritizes profit over people, and in doing so uses nationalistic pursuits as an excuse for over exhausting the nation’s youth in an unproductive and damaging manner.

Homework was first popularized in the midst of the Cold War when America’s priorities revolved around doing anything and everything to outperform the Soviet Union, whether in outer space or in the classroom. Students were given extra work to complete after school with the intention of preparing them for battle in a seemingly never-ending conflict centered around intimidation. In the interest of exploiting societal norms for nationalistic pursuits, young people in school were expected by the government to outperform their counterparts in the Soviet Union, and in doing so set a national precedent for the future of America’s approach to education. Once it was determined that giving children extra work was socially and culturally accepted, taking advantage of the opportunity to ask more of teenagers and further push them towards seemingly unattainable benchmarks and standards became an irresistible temptation.

Since the mid 20th century, homework has only grown more and more labor-intensive. As the middle class slowly disappears, and working in a factory or on a farm becomes less and less frequent, homework is designed to place students on a corporate conveyor belt, leading them toward careers that fuel the engine of capitalism on which America is dependent. Driven by profit, the College Board created standardized testing that numerically ranks students in a narrow representation of the individual, providing the opportunity for more studying at home that ends up costing extra amounts of money. A Stanford University study surveying over 4,000 students in California said that 56 percent of students surveyed “considered homework a primary source of stress,” which can “hinder learning, full engagement, and well-being.” With endless amounts of busy work and at-home learning, students are being trained to complete work for the sake of a number or a letter, creating an environment in which the actual learning takes a back seat to the numerical standard.

The question begs to be asked: what would happen if we were to take away homework? To examine this notion, one does not have to search very far. Consider Finland, a country that has a strong opposition to the concept of studying outside of school; in a recent study, it was confirmed that, “two in three students in Finland will go on to college,” which is the highest rate among European nations. Finnish children and teenagers, not tied down by homework, have time to explore their interests and indulge in learning as an experience to look forward to, rather than a duty. Finland, a socialist country and pioneer in the movement for no homework, is ranked first in education worldwide, part of which has to do with its non-corporate-centric manner of examining learning and achieving that correlates with socialist values. With equal access to educational resources among citizens, a high moral and economic respect for teachers, and an emphasis on nurturing collaborative rather than competitive students, Finland’s model of learning proves that a better option is both feasible and successful. The country has been joined by many other individual institutions around the globe, and the movement has, for the most part, proved fruitful among those who put more effort into raising the quality of education in school and trusting students to find productivity and prosperity in their free time.

In the interest of proactivity, Scituate High School has a chance to make a difference. Although homework-free weekends were semi-stress-relieving (what happened to those, by the way?), they were not enforced, and homework would usually find its way in. However, with a simple experiment, the concept of homework and its effects on students could be examined, and Scituate administration, teachers, parents, and students could see the subsequent shift in priorities in full color. All that would be asked is one week, Monday to Monday, of no homework. This would be greatly enforced throughout the school, no matter the level of class or the teacher instructing or the amount of material needed to cover. This one week would consist of absolutely no assignments that went beyond the hours of class time, allowing students to use this time to try something new and invest in something they care about. At the end of the week, there would be a survey, asking the students about changes in mental health, stress levels, and benefits of the experience.

From there, one would be able to see the positive (or negative) effects of taking away homework and perhaps implement the philosophy of “less is more” and “quality over quantity” in a more regular setting. As an institution that emphasizes growth through learning, Scituate has the chance to make a huge difference in teenagers’ lives by trusting the students to take the reins of their own learning journey. It might be an idea that is outside of our comfort zone as a community, but one must recognize that no positive change has ever occurred through being comfortable. After all, Gandhi said, “You must be the change you wish to see in the world,” and the change is begging us to catch up.